Neural Engineering

The ability to control prosthetics and computers with thought has been a seminal breakthrough in neuroscience and biomedical engineering. The most impressive technology is based on invasive medical devices–multi-electrode arrays–which are surgically placed in the brain. As a graduate student in Tracy Cui’s lab and post-doc in TK Kozai’s lab at University of Pittsburgh, my research was to develop imaging and image processing techniques to understand how the the implantation of these devices affected the health of the surrounding brain tissue. The following are some highlights from that work.

Mapping neuronal damage during electrode implantation

An electrode device needs to be CLOSE to a neuron in order to distinguish its individual activity from the billions of other neurons. To achieve this, the device typically shaped like a needle or dagger and is punctured through the brain tissue. As the device enters, it breaks blood vessels, pulls connected neurons appart, and creates mechanical strain on the cells. Part of my research was to map out this damage using transgenic models to visualize neural activity during implantation. Here’s what this looks like (the electrode array looks like a black fork):

The bright area is a marker for neural activity. The fact that it gets very bright during the implantation reveals a potential source of over-stimulation and damage to the neurons. A different imaging technique can allows us to visualize individual cells during implantation:

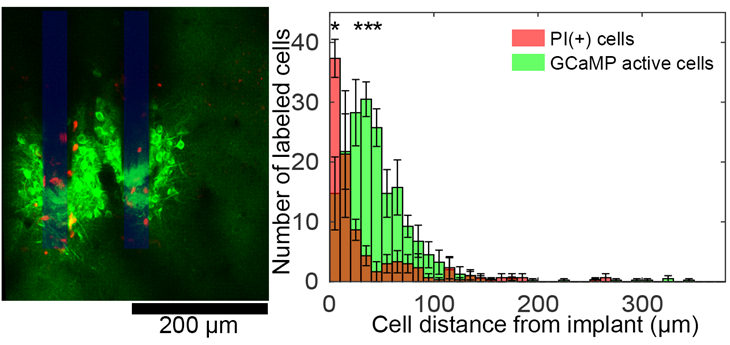

We used a dye for dead cells to figure out that only a subset of the high-activity cells were seriously compromised (shown in red below) in the implantation, but it’s unclear if the surviving high-activity cells would have long-term complications.

Ultimately, this study and technique can help us measure how new electrode devices and new implantation strategies could affect the health of the neurons that they are trying to listen to.

Controlling the inflammatory reaction to implanted devices

The same imaging techniques described above can also be used to study the inflammatory response to implantation. The body treats the electrode like a splinter–it tries to get rid of it. While this has long been appreciated, we don’t know too much about what triggers the inflammatory response and if we can control it.

After an electrode is implanted in the brain the local inflammatory cells of the brain–the microglia–react by extending their arms toward the device. They cover the surface of the device and eventually migrate toward it (evident to the right of the labeled electrodes).

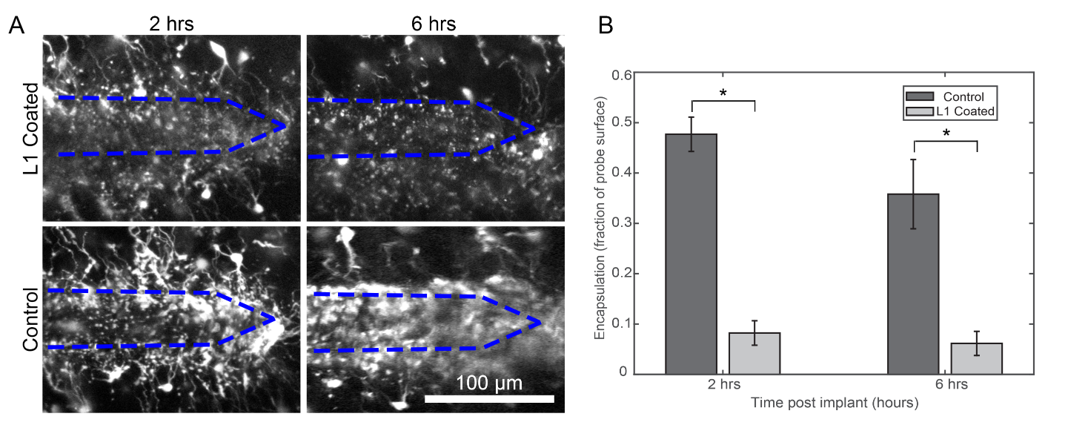

Using these imaging techniques, we were able to establish that the microglial reaction can be reduced by coating the device in different biomimetic materials or pharmacological interventions. Below, you can see a comparison of the inflammatory cell coverage of electrodes (outlined in blue) with or without the coating material:

The electrode is implanted into the brain, but parts of the electrode stick out of the brain. This region has a distinct inflammatory reaction, but we were able to see that the cells here were able to still crawl on the device and potentially migrate down into the brain.

This technique can help to direct electrode design to minimize and control the inflammatory response.

Improving Brain-Computer Interface feedback through electrical stimulation

Next-generation brain-computer interface tools incorporate sensory feedback to improve user-control. For example, with a brain-computer interface controlling a prosthetic arm, sensory feedback can help the patient to “feel” what the arm is touching. This is done by electrically stimulating the sensory neurons associated with the hand. My post-doctoral research used imaging techniques to understand how different patterns of electrical stimulation could cause different types of neural activation. By patterns, take the following example:

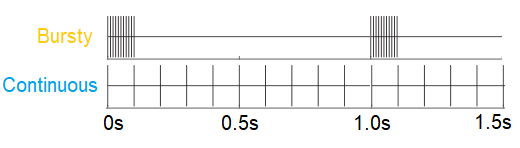

Each tick is an electrical waveform that can depolarize a neuron. Both the top and bottom stimulation patterns have the same number of ticks, but the ticks on the top pattern are more “bursty” while the bottom pattern is “continuous”.

In the following video, we are watching a “bursty” and a “continuous” stimulation trial overlaid on one another. Oranger cells were preferentially activated during the “bursty” stimulation, while blue cells were preferentially activated during the “continuous” stimulation:

This shows that the same amount of charge delivered from the same exact electrode site can be shaped to recruit a different set of neurons. Clinically, this may mean that the same stimulating electrode can generate different sensations simply by altering the temporal pattern. We hypothesized that this effect was mediated by playing on the different firing rates of excitatory and inhibitory neurons.

This is the short version of my research. For my publication, see my Google Scholar page. Please feel free to reach out if you’d like PDFs for any of these papers.

Leave a comment